New figures show extremely powerful painkiller W-18 has been detected in 30 drug seizures this year, up from three in 2015.

As Canada struggles with a deadly epidemic linked to the powerful painkiller fentanyl, a new and potentially more lethal threat is already emerging.

Invented in a University of Alberta laboratory in 1981, the drug known as W-18 was designed as a non-addictive painkiller. It was patented but never developed by pharmaceutical companies for public use, yet someone is manufacturing it.

When the drug was patented, testing on mice showed it was 10,000 times more powerful than morphine, according to Health Canada.

“This suggests a potentially severe risk for harm to individuals,” the agency warned this summer in passing regulations that will soon make W-18 a Schedule 1 drug under the Controlled Drug and Substances Act, along with the likes of heroin and cocaine.

Health Canada noted there was “limited scientific information” available about the drug though more testing is underway.

Despite the risks, W-18 is showing up with more frequency in police drug hauls, according to Health Canada figures obtained by the Star.

In 2015, there were just three drug seizures by Canadian police that tested positive for W-18 at Health Canada laboratories.

So far in 2016 there have been more than 30 positive tests — for an average of more than three times a month, according to Health Canada. Fifteen cases occurred in British Columbia and 14 in Alberta.

But the drug has also started showing up in Ontario, where W-18 has been detected on two occasions so far this year. Both cases involved drug seizures made by the Greater Sudbury Police.

One resulted in three men — from Sudbury, Toronto and Manitoulin Island — being arrested May 12, according to a spokesperson for the force. The spokesperson declined to provide details on the other case because the Health Canada laboratory results had not yet been confirmed to investigators.

The emergence of W-18 and other obscure synthetic drugs is due to the squeeze by law enforcement on more prominent or easily accessible drugs, police say.

An RCMP intelligence report published this month attributed the rise in fentanyl use, and the record number of deaths and overdoses, to the removal of the painkiller OxyContin from the market in 2012.

As law enforcement now clamps down on fentanyl production, W-18 is considered to be “at the high end of the threat spectrum” to take its place, the report said.

That view is shared with frontline officers who have found W-18 in raids of clandestine fentanyl laboratories, including acting Sgt. Jill Long from the drug squad of the Delta Police Department, which covers a suburb of Vancouver.

“It could be dependent on how fentanyl and fentanyl analogs are controlled or if there’s a major seizure — that always causes a push of other drugs to move onto the scene,” she told the Star.

“If that’s going to make (drug manufacturers) more money because fentanyl is not available then I think we would see a push to that.”

British Columbia has declared a health emergency over the fentanyl crisis, and there is pressure to do the same in Alberta. The Quebec government has been asked to better control prescriptions of opioid painkillers for fear of being swept up in the deadly drug wave.

This summer, Ontario became the first province to stop paying for high doses of morphine and fentanyl in a bid to prevent addiction and overdoses. But the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police warned a few weeks ago that the province is already facing a “chronic opioid crisis.”

The group said that its current preoccupation is “bootleg fentanyls” showing up in pills and powders, sometimes disguised as Percocet and OxyContin or mixed in with heroin and cocaine.

It included W-18 in that group even though tests have shown the powdered chemical is not, in fact, an opiate as was originally thought. Authorities have been treating it in the same manner because W-18 is often produced to look like fentanyl or oxycodone pills. Most often, the drug has been obtained from Chinese distributors for consumption or to be trafficked here in Canada.

Public health officials are also warning that because of its distinct chemical nature, users who overdose on W-18 may not respond to naloxone, which is now the standard emergency treatment for opioid overdoses.

“All the reports from 2016 in terms of seizures, in terms of anecdotal reports and early evidence from emergency medical services point to a rise in opioid overdoses,” Michael Parkinson, a member of the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council, a community safety group, told the Star.

Ontario is hampered in detecting and responding to the problem because there is a delay in reporting on toxicological results from the provincial coroner’s office, said Parkinson.

“Coroner data is two years past expiry and what we really need is a system similar to what’s in place for measles and influenza outbreaks where we know almost immediately and are able to respond quickly with interventions that will prevent death and injury,” he said.

Even in locations where fentanyl abuse and deadly overdoses are rampant, it is taking months to detect the presence of W-18 in the drug supply.

The Delta police came across an alleged batch of W-18 at a suspected fentanyl laboratory in March but didn’t know what they had until the lab results came back in June. Police said it was being manufactured to appear to users like heroin or oxycodone.

A 35-year-old Calgary man who had died in March of a drug overdose was identified as the first known W-18-related fatality only when the lab results came back in May, showing that he had W-18, heroin and a more toxic form of fentanyl in his system.

There may other, unknown W-18 fatalities because no standard screening tests currently exist. There would need to be solid suspicions that W-18 was present for a specific analysis to be carried out, Alberta’s chief toxicologist, Dr. Graham Jones, explained in a public statement in May about the Calgary death.

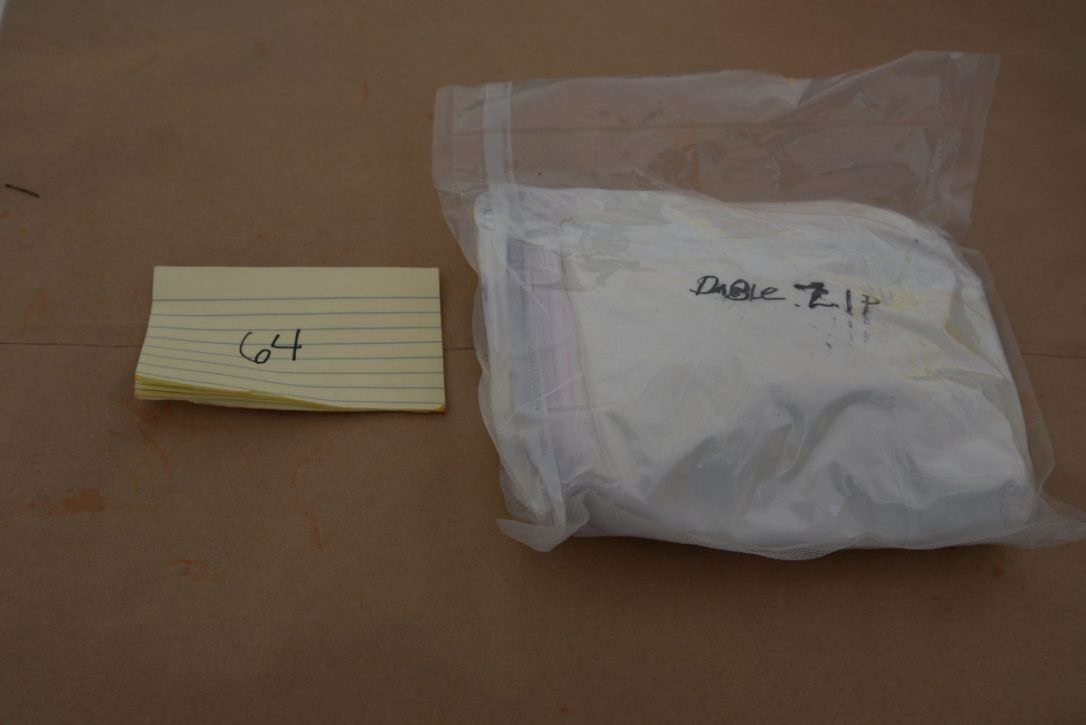

This summer, in one of the first W-18-related court cases to have resulted in a criminal conviction, agents with the Canada Border Services Agency at the Montreal airport seized a package that had been sent from China, according to police and the Crown.

The contents of the package were labelled synthetic rubber, Crown prosecutor Annabelle Racine told the Star. Tests showed the pale yellow powder which weighed 2.5 grams and was stored within three ziplock bags was actually W-18.

Undercover RCMP officers carried out the delivery at a home in Laval, north of Montreal, and later arrested a 39-year-old man. Ryan Challenger pleaded guilty on July 22 to violating regulations of the Food and Drug Act related to improper labelling. He has been sentenced to 30 months in prison and additional time for an outstanding charge of dangerous driving and breach of probation, according to a Correctional Service of Canada document dated Aug. 2 that outlines Challenger’s punishment.

Racine said Challenger testified at his sentencing hearing that he owned a company that imports chemicals and that his intent was to provide W-18 for a customer.

That in itself — dealing in an unapproved drug — is illegal. But it will take until Nov. 28, 180 days after Health Canada’s regulations were passed on June 1, for police and prosecutors to get the greater powers and stiffer penalties to clamp down on this new and little-known drug.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.